In the year of our lord 2023, I think most anime fans, in the know, are aware of both Mamoru Oshii and Rumiko Takahashi. The former being the legendary director responsible for classics such as Angel’s Egg, Jin-Roh, the entire Patlabor franchise, and of course Ghost in the Shell; The latter being the prolific writer of shojo manga classics such as Inuyasha, Maison Ikkoku, and Ranma ½; so on and so forth. Both veritable icons in the industry with incalculable numbers of works and creators influenced by them. Despite the obvious canyon-sized gulf between the stories they are known for, both their careers share a common nexus point. That point being a silly little gag series called Urusei Yatsura.

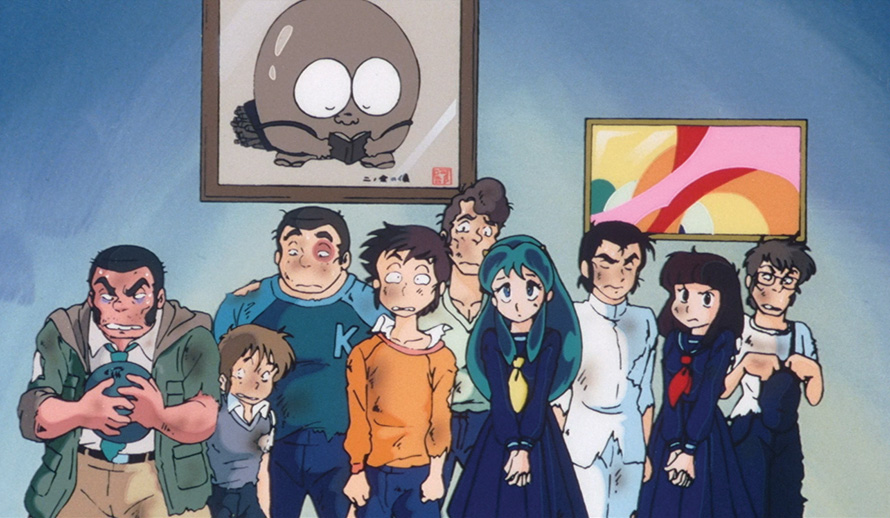

Rumiko Takahashi started writing Urusei Yatsura in 1978. It’s a comedy romance manga about a high schooler named Ataru Moroboshi, and an alien princess named Lum. After a complicated set and ridiculous set of circumstances, she comes to believe that she is Ataru’s wife after he accidentally proposes to her. As was customary for popular manga of the day (and currently as well) an anime was produced. In 1981 the anime first aired with the then-relatively unknown Mamoru Oshii as the series’ chief director. Oshii brought directorial finesse and a sense of grandiosity to the series. The episodes were mostly straight adaptations of the chapters written by Rumiko Takahashi. However, Takahashi’s jovial free-wheeling character archetypes and Oshii’s light arthouse sensibilities created a bizarre yet compelling combination. He stayed on the show for the first 106 episodes of its run; directing 24 episodes himself and the first 2 films.

That brings us to the key topic for today. That being the second film, Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer. Unlike the first film, Beautiful Dreamer was written entirely by Oshii himself, and you can see his handprints all over it. Anyone who loves films like Ghost in the Shell or Angel’s Egg owes it to themselves to watch this movie, as many techniques used there can be found here as well. Albeit, in a much lighter more family-friendly overall package. There are many narrative diversions where the story/tone flips on its head and transforms into something entirely new. It deals with heady themes with certain parsley animated scenes featuring purposefully didactic monologues on whatever themes Oshii was interested in at the time. There is an avalanche of surreal imagery and visual metaphor that would make any film hard to follow even in one’s native tongue. It’s a multilayered complex film inside one of the most deceivingly approachable packages it could be part of.

That’s a big reason why I was so interested in experiencing this film without subtitles to guide me. On the one hand, while it is quite easy to grow accustomed to reading and watching at the same time; (so much so that one barely notices after a few minutes) it is true that Subtitles can sometimes distract from the imagery of a given piece of visual media. I wanted to look at this film with new eyes and really take in the rich animation on display. I have already seen this film multiple times, so I was not too worried about being lost. On top of that, despite the complex narrative, it’s still fundamentally aimed at younger audiences with themes mainly geared toward teenagers. This made it a great start to this project. It’s a good test run to see how well-crafted films are able to, not only convey narrative, but also motifs and ideas through cinematic tools other than dialogue.

Admittedly some scenes were a bit difficult to parse, especially the ones heavy on dialogue. This includes most of the scenes involving the character Sakura. Sakura is the school nurse and serves as a sort of mentor character throughout the film. As such most of her scenes end up being rather expository. In one key scene, Sakura is unknowingly confronted by the main antagonist of the film, Mujaki. A “dream” spirit that has trapped the cast in a time loop. Forcing them to repeat the same day over and over, without them noticing.

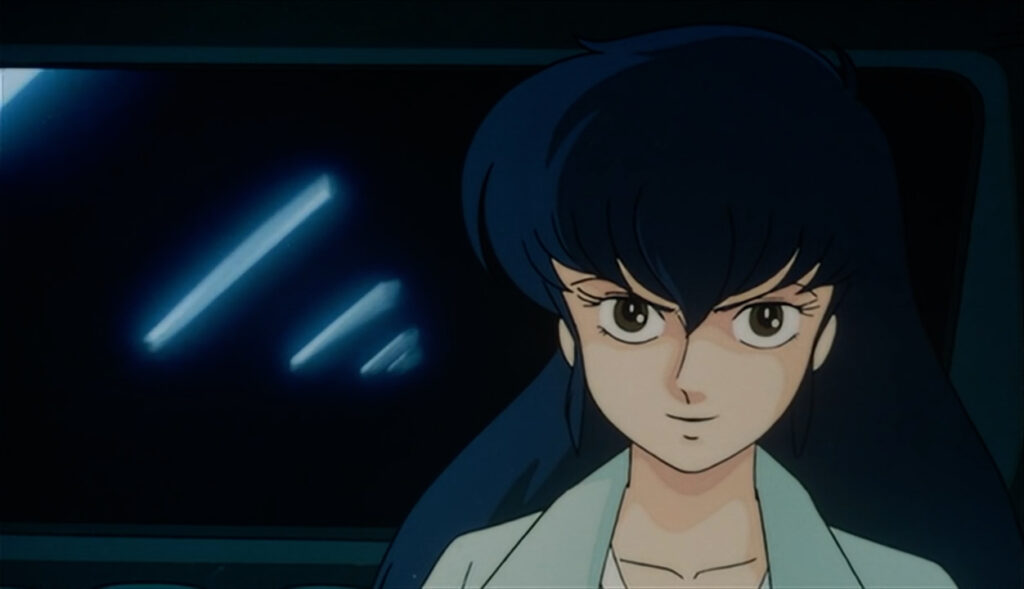

In the scene Mujaki is disguised as a Taxi driver, driving Sakura back home. After a while, Sakura asks why the drive is taking so long; prompting a perhaps a bit pretentious and dubiously set up elongated dialectical discussion on the relativity time. These introspective almost Brechtian philosophical debates between characters would become commonplace in Oshii’s later films such as Ghost in the Shell or Patlabor 2. They are very low-energy scenes with animation that focuses more on the background. It’s not necessarily cinematic and it’s certainly hard to parse even if one does know the language, as it does deal with surprisingly complicated concepts for a children’s anime.

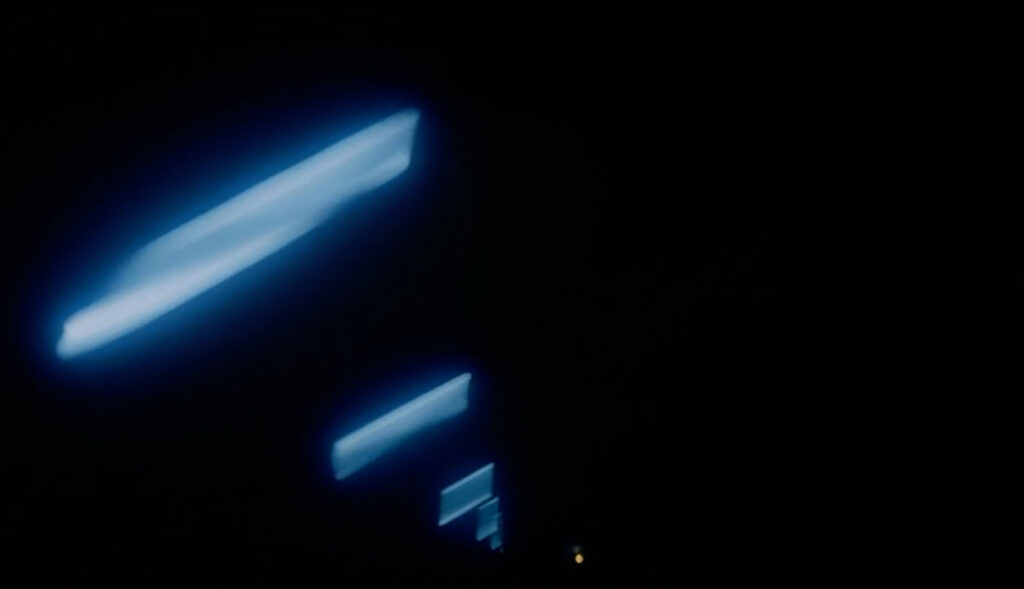

On the surface, the visuals do little to help relieve one’s confusion. Most of the scene consists of what is essentially the animated equivalent of a still shot. We only see Sakura and Mujaki sitting in the car, talking; as the street lights go by, in the background. However, it is in those street lights that meaning is found. As the drive continues we see them pass by one after the other, almost in a rhythm. Mujaki and Sakura are partially draped in shadows. The streetlights remain in the background but they become the clearest source of light in the scene. The street light becomes a time loop themselves; endlessly repeating. A visual metaphor for the cyclical nature of how the characters are experiencing the current day.

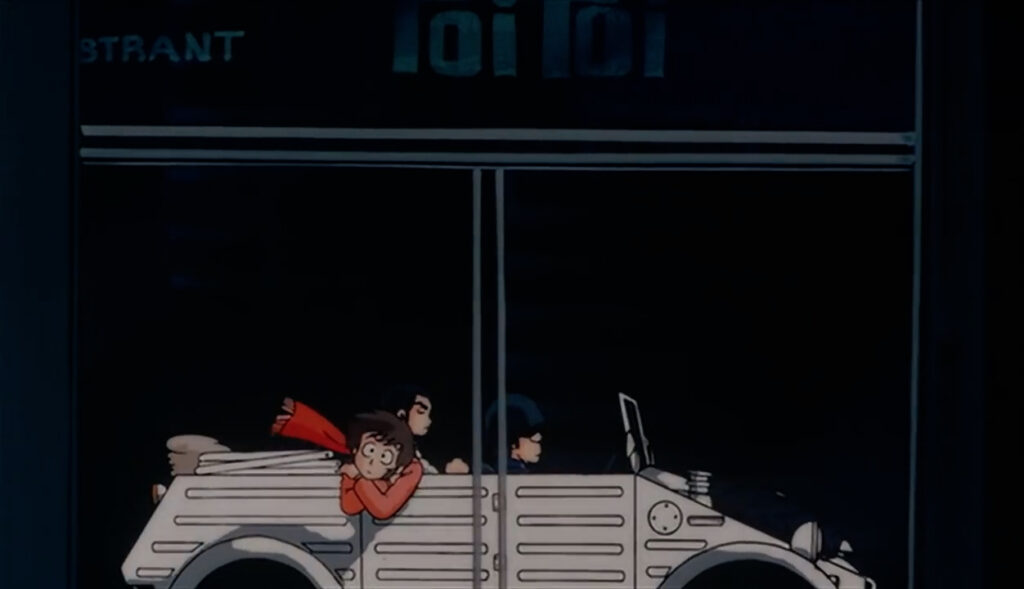

In fact, driving and the open road serves as a metaphor for time at many moments in the film. Near the beginning, there is a confrontation between our protagonist Ataru and his rival Mendou. Mendou is driving Ataru back home and lecturing him about his behavior at school. Like Sakura in the Taxi, the streets are curiously quiet and barren. All Ataru can do to pass the time is stare out at the windows of the passing buildings. There is a protracted shot of Ataru staring at the windows as the car drives on. We see the animation loop as buildings pass on by; Ataru’s reflection looping along with them.

In both of these scenes, The world outside the vehicle is repeating. As Mujaki comments “Maybe time slows down when you’re in a Taxi.” Anyone familiar with long drives, especially ones in the late hours of the night and early morning has personal experience with this. Time is relative on the road. You exist in your own little pocket dimension, where everything slows to a crawl. The mundanity of it all consumes you. I myself am no stranger to long road trips and arriving home far past the time everyone else has gone to bed. For me, it was always the trees. Driving on endless stretches of straight roads as a near-infinite forest of trees seems to stretch forever into the horizon. It’s almost hypnotic.

Oshii not only captures the madcap plot of time loops and pocket dimensions, but also the film’s themes, just by subtly honing in on the almost universal human experience of long late-night drives. Even if you can’t understand a single word of what is being said, you can feel it in the atmosphere. It may call to mind similar experiences of your own late nights on the open road.

The taxi scene also contains another clue into the mysteries of the film. When discussing the taxi ride, Mujaki alludes to the Japanese folktale character Urashima Taro. In fact, the story of Urashima Taro is referenced a number of times throughout the film. These references to Japanese folklore are par for the course in the stories of Rumiko Takahashi. Many of Takahashi’s stories deal with Japanese folktales, but why this Urashima Taro in particular? Urashima Taro is an old tale about a man of the same name. One day he saves a small turtle from being attacked by a group of young children. The following day a larger turtle comes to the surface to thank Taro. As a gift, he gives Taro gills and brings him to a magnificent undersea palace to meet princess Otohime. Taro stays with the princess for 3 days; before departing Otohime gives him a mysterious box but warns him not to open it. When Taro returns to the surface, he is distraught to learn that 300 years have passed since he last left. In his despair he opens the box and immediately ages 300 years, Otohime laments from the water that she warned him not to open the box, as it contained his old age.

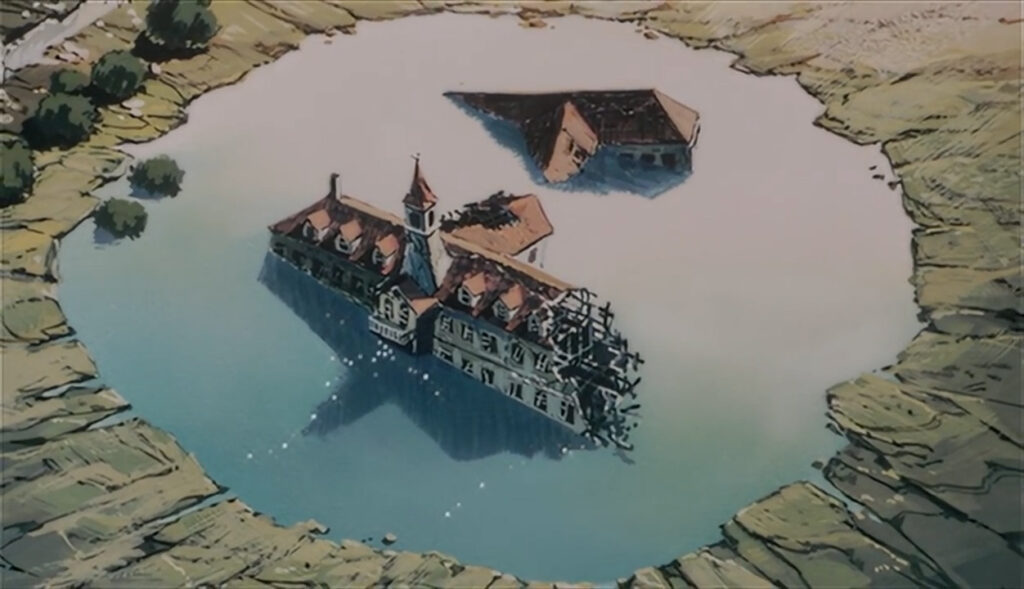

There are some pretty obvious parallels between this rather dark fairytale and the themes of the film. Beautiful Dreamer goes further and literalizes this metaphor near the end of the story. In the climax, It is revealed that our cast has become trapped in the series mascot Lum’s dream. Earlier in the film, she talks wistfully about how she would like to spend forever in these youthful days with her friends. Thus, in her dream, everyone is stuck repeating the same day. Like Taro spent 3 magical days in an underwater kingdom, unaware he was there for hundreds of years. The cast spends one eventful school day with each other, unaware they have been doing this for months.

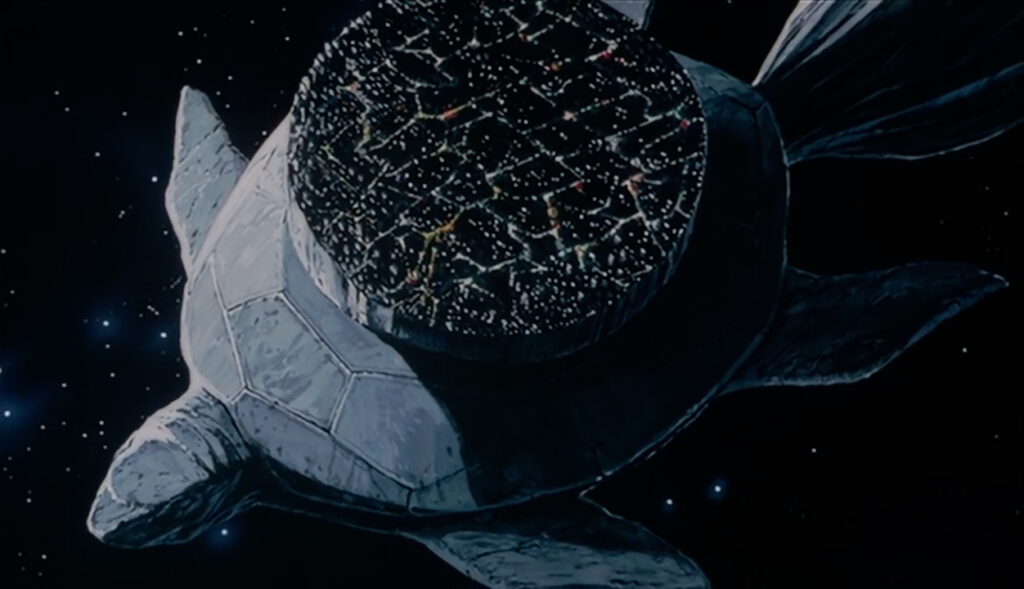

The metaphor is at its most blatant when the cast finally leaves the city. In Mendou’s Jet, they fly into the sky. From this higher vantage point they notice that their hometown is no longer connected to the rest of the world, but now floating in space suspended on a large turtle (I told you the imagery gets wild in this). That is as literal a reference to the Urashima Taro myth as you can get. Like how the turtle brought Taro to an undersea palace, these characters are being carried to their own magical dreamland on the back of a turtle.

Like the rest of Takahashi’s series that the movie is based on, Beautiful Dreamer uses common Japanese myths and folktales to tell its story and reveal more about its characters. Anyone familiar with these myths will be able to pick up on the imagery being displayed without needing to hear the characters explain it to them.

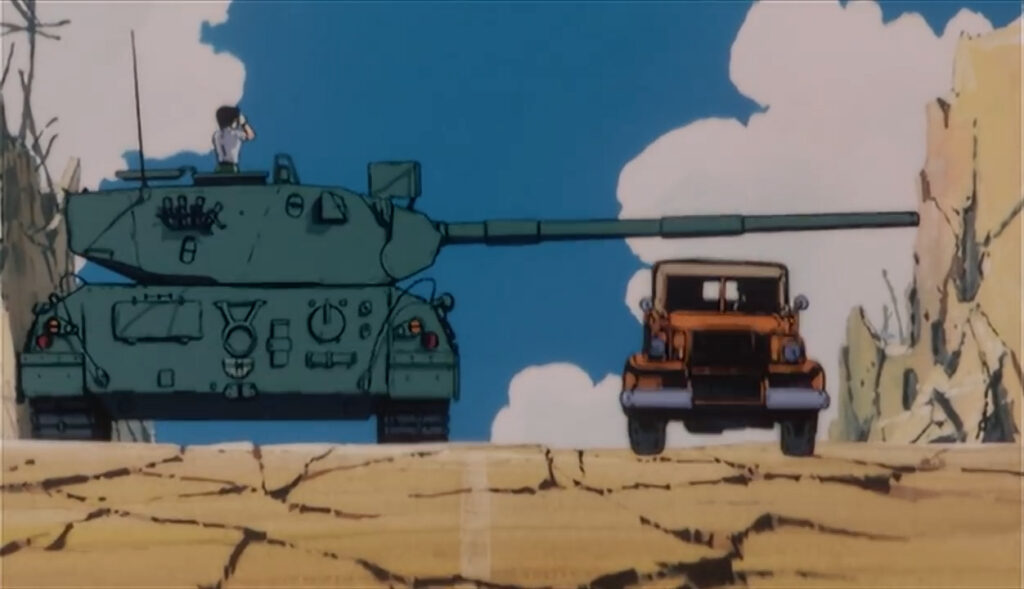

As the days continue the city itself starts to crumble. All the people that are not primary characters disappear. This marks the key genre and tonal shift in the film. As the school and city slowly change into rubble, the film takes on the aesthetic of a post-apocalyptic survival film. It’s still a silly animated teen comedy at heart, but the setting and many of the genre conventions seem to share more DNA with Mad Max than Breakfast Club.

This is not the last time the film’s genre walls start to completely break down. Once the scope of the story is revealed to Ataru. He is sent on a veritable nature tour of new dreams as Mujaki tries to get rid of him. Naturally, all of these dreams take the form of classic Hollywood films. Films like 2001: A Space Odyssey or Frankenstein. These references help ground the film and guide the viewer through its pretty wild plot and drastic tonal shifts. Intertextuality is used to keep things light, but also give the audience a visual jumping on point to better engage with what is going on. This includes story references from Urashima Taro to Godzilla.

That’s at least part of how I was able to keep track of the insanity on display. Beautiful Dreamer is jam-packed with mesmerizing moments of unreal animation that I didn’t have time or justification to talk about here. I have seen the movie multiple times at this point, and every time there are multiple scenes I forget about entirely, that blow me away all over again. It’s not that they are unmemorable, far from it. It’s just that there is too much in this one movie to completely internalize. It’s filled to the brim with bizarre imagery and mind-bending scenes. I didn’t have time to touch on the flying elephant that grows huge and devours the dream world, or the Giant unsettling statues of the humans ejected from the dream.

You’ll just have to find all that stuff for yourself. The film is available dubbed on amazon prime, and the dub is quite good from what I have heard. Sadly, it is more difficult to get one’s hands on the original Japanese version with subtitles. That is one of the key motivators in starting this project. You can buy the blue ray if you want to experience the film in its original language, and I highly recommend that you do. It’s one of my favorite films and I would love it if more people could get the chance to hopefully love it as I do.

One reply on “The Beautiful Dreams of Urusei Yatsura 2”

Excellent overview of the film! I want to add that the Urashima Taro parts are translated, both in the dub and in English subtitles, to references of Rip Van Winkle, the American folk hero that gets plastered, falls asleep in the mountains, and sleeps for twenty years to find a post-Revolutionary America. The localization is very clever, connecting a similar story shared by two cultures, but kinda makes a mess out of the turtle imagery leftover. When I first watched the movie (with subs). I thought it was more of a reference to myth rather than something further connected to the movie’s symbolism.