It has been exactly a decade since famous Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki released his 11th and “final” film The Wind Rises. Set during World War II the film followed real-life Fighter jet designer Jiro Horikoshi. The film is a melancholy and beautiful look at the artistic process filtered through the lens of that horrific conflict; Serving both as a tribute to the kinesthetic and mechanical process of engineering, while also serving as a tragedy for when such passion eclipses one’s ability to see the human element of one’s artistic obsession. The movie was somber and self-reflective and all around the perfect swan song to this legendary filmmaker’s storied career.

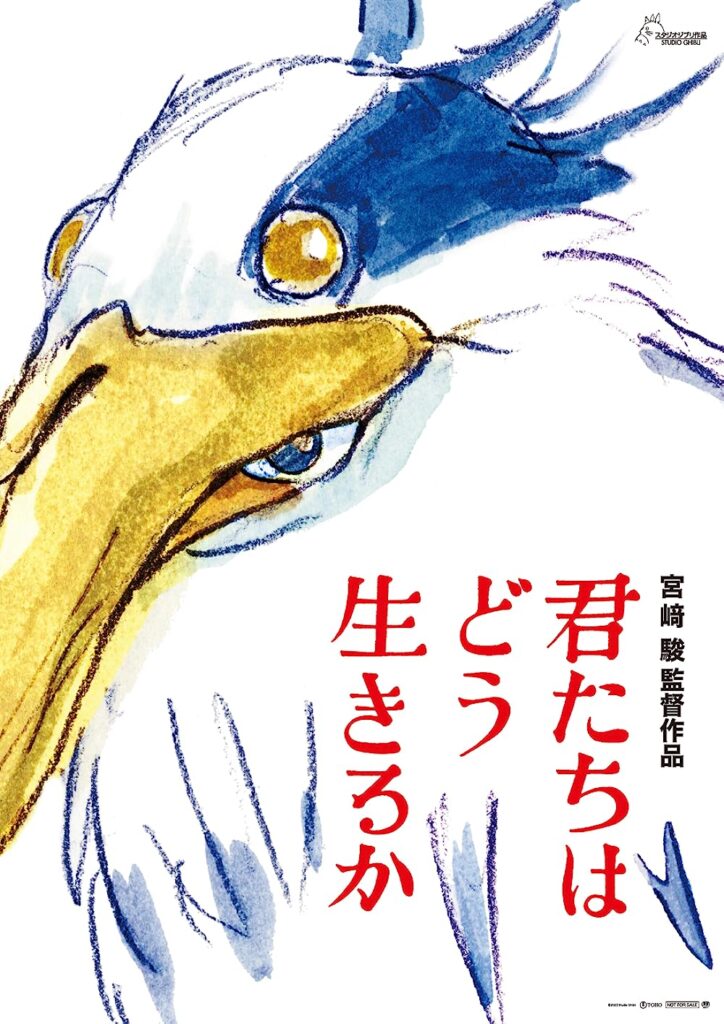

So imagine everyone’s shock, when at the spry young age of 82, Miyazaki embarked on a new cinematic journey, resulting in the newly released 君たちはどう生きるか (How Do You Live?) or as it is beginning localized to in the West as The Boy and the Heron. Throughout this review, I will begrudgingly refer to it as the English title for clarity’s sake.

Also in regards to spoilers. I will try to maintain some degree of secrecy however the marketing for the film (or lack thereof) makes this a tad difficult. Ghibli came to the bizarre but interesting decision to not give any plot summary or release any trailers for the film beforehand. While this has created an engrossing sense of mystery around the project, it has left me with a not-insubstantial conundrum.

For this review, I have decided to talk about the film as if it did have a trailer, and only speak on the matters I believe would have been shown within. I’ll also vaguely discuss other elements of the picture, without diving too deep into serious plot details. However, if you wish to go in completely blank like I did, here is the station to disembark at. Just leave the trolley knowing that this is a very good film, well worth anyone’s time.

The Boy and the Heron is the story of a young boy named Masato. Masato’s mother is killed during the Tokyo firebombings, and his father and he relocate to a wealthy villa in the Japanese countryside. There his father remarries his dead wife’s sister Natsuko, and the two expect a baby together.

What initially appears to be a grounded coming-of-age tale, soon morphs into something more frightening and fantastical. At first subtle with the appearance of the unsettling eponymous Heron, the film balloons in scope and magical wonder in ways I dare not fully give away here. Just know that if you love Ghibli for its creative fairytale words and endless visual ingenuity, you will not be left wanting by this picture.

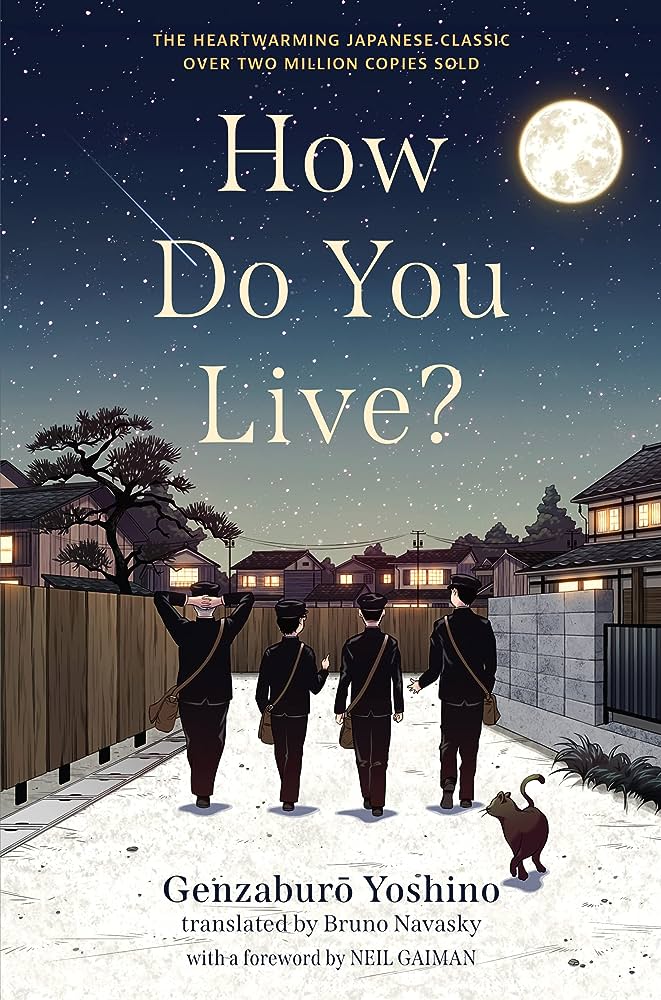

The film is in many ways defined by its influences as much as it is by itself. The film’s Japanese title is based on a book of the same name. The book How Do You Live? plays a minor role in the story of the film itself, however, its main contribution is to serve as a parallel to the tale unfolding. The novel was written on the eve of World War II, during Japan’s imperial rise to prominence. The novel’s author, Genzaburo Yoshino, was arrested during this time for being associated with known socialists. After over a year in prison, he had had his release secured by a friend. He then went on to work with said friend on an ethics book for young readers.

This book is what eventually became the narrative story How Do You Live? The book follows a young boy named Copper who abandons his life in Tokyo when his father sadly passes away. During this time he forms a bond with his Uncle as he learns life lessons about growing up and different ways one can choose to live. It was a controversial book that was meant to teach kids self-reflection empathy, during a time when the nation was drifting further and further into extreme nationalism.

The similarities between the novel and the film are undeniable, while not a direct adaptation, the film hits on many of the same characters and story beats plus the inclusion of more fantastical Ghibli moments. Like the novel, the film is the story of how a young boy learns to come to terms with the world and its many complications through the death of a parent. Both works also can be quite episodic at moments, involving our main character meeting someone new and learning where they exist in the vast ecosystem of the world and their way of life.

There are many times in the film where characters are presented as antagonists, but after learning of the characters’ circumstances Masato is forced to develop empathy for them and understand their philosophy. The climax of both the film and the novel is understated in that they revolve around our character’s internal conflict, as their final decision involves the characters needing to come to terms with their own failings and learn who they are and how they want to live their life.

There is another, much more pressing story that runs parallel to the movie. That being Miyazaki’s own childhood. This is by far the most autobiographical entry of his filmography, with many aspects of Makoto’s life mirroring Miyazaki’s. For example in the film Makoto’s father is an airplane engineer, like Miyazaki’s own father. While not directly about the war, the film still inseparably takes place during the war, with the opening scene being a harrowing portrayal of the Tokyo fire bombings. Portrayed in a scratchy rough art style not seen in the rest of the film. In real life, Miyazaki recounts how his earliest memories were that of bombed and destroyed cities.

Now this is not like say Spielberg’s The Fabelmans. It is nowhere close to a one-to-one retelling of Miyazaki’s life, and I don’t want to get overly Freudian with this analysis and say the main character is supposed to represent him. With that said, These details certainly can’t be ignored. Miyazaki surely meant it when he said he planned to retire after The Wind Rises, but he came back for this film. and the reasoning is quite touching. In an interview with the film’s producer Toshio Suzuki, Suzuki said

“Miyazaki is making the new film for his grandson. It’s his way of saying ‘Grandpa is moving on to the next world, but he’s leaving behind this film.”

Toshio Suzuki

You can see how this is a very personal project. Encapsulating aspects of the man’s own life, of the works that inspired him, and even some of the works he himself has made. The proverbial Heron here can be seen as a bizarro reflection of staple Ghibli characters like Totoro.

Trying to nail down a precise allegorical equivalent is impossible. Of course, you can see Makoto as a director stand-in, but there is another character in the film constantly referred to as “grandfather” who is also clearly meant to stand in for Miyazaki. the characters and motifs bleed into each other, mixing and matching into an endless array of readings. The film borrows from so much Japanese, folklore, national history, and art history and recontextualizes it into its kind of fairytale. Far from being a greatest hits collection, the movie’s greatest strength is how it complicates its own history and symbols to force the audience to decide for themselves what they want to take from it.

Regardless, the soul of the film remains the same. This a film about taking in all these possibilities, all these life philosophies, and finding your own way. Learning who you are, and deciding for yourself how you are going to live your own life.